We had arranged with the folks at Hotel Chobe Marina in Kasane for a guided day trip across the border to Zimbabwe to see the famous Victoria Falls. One of the hotel staff accompanied us to the Kazungula border post, about a 20-minute ride away. Four countries meet at Kazungula: Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

We crossed the border into Zimbabwe, completed immigration formalities, and were met by our guide, Stanley. Seejo and I already had visas, so our entry was quick. My mother, Dwiti, and Asif needed to get theirs, which turned out to be an unexpectedly painless process. We paid $100 USD per visa, got the stamps, and were soon on our way with Stanley. It was another 45-minute drive through fairly empty roads, with the occasional giraffe or monkey crossing, until we reached the parking lot near the Wilderness Travel office by Victoria Falls.

Even from a distance, we could see the mist rising and curling like smoke into the sky. I remembered reading that the locals called the falls “The Smoke That Thunders,” and it felt like a perfectly apt name. Once Stanley parked the car, he handed us a few scruffy-looking raincoats and went to get our tickets for the Victoria Falls State Park. It was a bit tricky trying to maneuver the raincoats over our handbags, which we couldn’t leave in the bus since they held our wallets, passports, and in Seejo’s case, his camera gear. It didn’t take us long to realize the raincoats were useless anyway since the buttons were broken and none of us could fasten them properly. We began our walk through the park from the foot of the Livingstone statue. David Livingstone was the first person from the western world to view the falls in the late 1850s. Recalling the famous explorer Stanley’s first meeting with Livingstone, I couldn’t resist taking a picture of our own guide, Stanley, beside the statue.

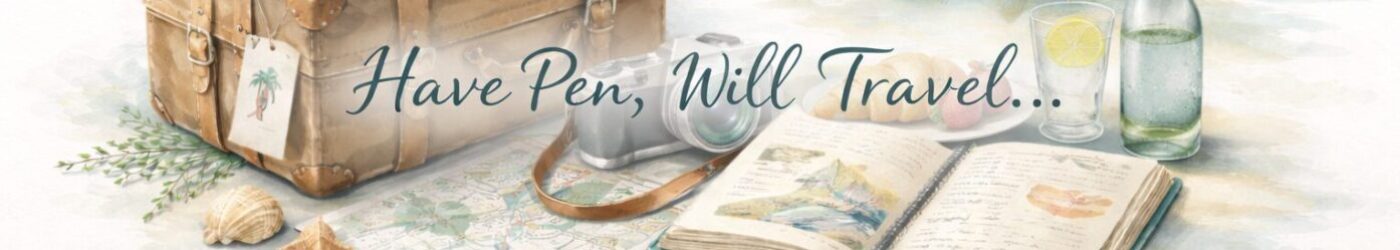

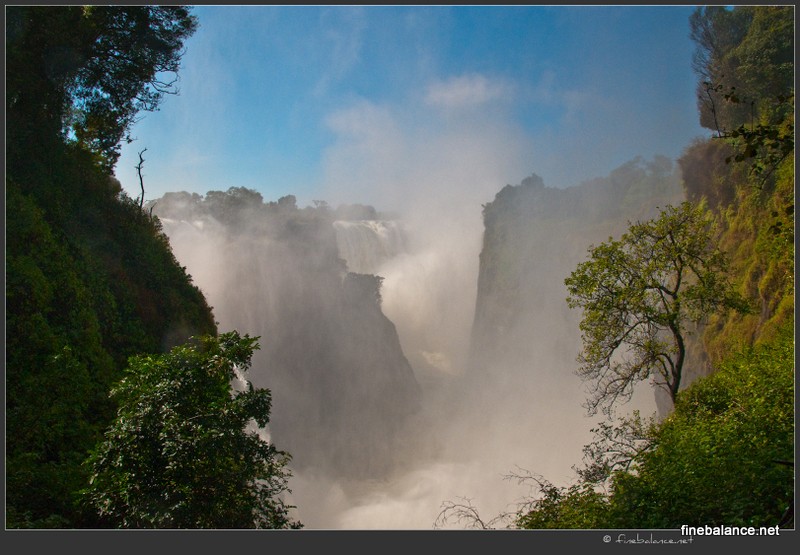

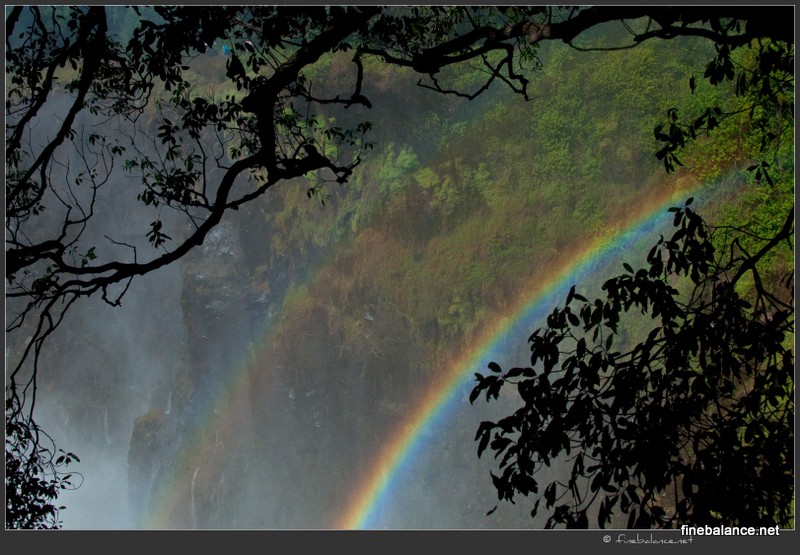

From there, we followed a guided loop. From the Zimbabwe side, four of the five major falls that make up Victoria Falls are visible. The first was the Devil’s Cataract, framed by two beautiful rainbows. To get a closer view, we descended about seventy steps to a point overlooking the cataract. The Zambezi River plunges through a series of narrow, high gorges with steep, almost vertical walls to create this incredible natural wonder. The water spray grew heavier as we moved between viewpoints until it felt like we were standing in a torrential downpour. Our old, hoodless raincoats offered little protection, and we were soon drenched. We could barely make out Livingstone Island between the Main Falls and Horseshoe Falls. When the wind shifted, we’d catch a ghostly glimpse of trees through the mist, but most of the time all we could see was a vast white curtain. By the time we reached the Horseshoe Falls viewpoint, the spray was beating down so hard that it was all we could do to keep our eyes open and our footing steady. Dripping wet but exhilarated, we paused at the bridge connecting Zimbabwe to Zambia. Our guide pointed out that the center of the bridge was a favorite spot for bungee jumpers, though none of us were tempted.

We stood for a while, simply watching the falls, awed by the sheer power of the water crashing below. People often ask me to compare Victoria Falls with Niagara. It’s difficult to rank two such magnificent natural wonders, but there are definite differences. Niagara is more accessible since you can drive right up to it, stay dry while admiring it, and enjoy light shows and boat rides like the Maid of the Mist. Victoria Falls, on the other hand, is Niagara’s wild, untamed cousin. The experience is raw and elemental. While Niagara surpasses Victoria in water volume, Victoria Falls is nearly twice as high and twice as wide. You don’t just see Victoria Falls, you feel it, and in our case, we quite literally wore it, soaked to the skin.

Stanley’s solution to our predicament was to take us to a local flea market. “By the time you finish shopping, you’ll be dry,” he said cheerfully. We weren’t amused since he had stayed dry under his umbrella while we were drenched to the bone, but our irritation quickly vanished once we arrived. The market was a colorful sprawl of local art: carved wooden bowls, stone figurines, masks, walking sticks, and intricately worked metal crafts.

My favorite purchase was a Nyaminyami stick, a short walking stick carved from top to bottom with intricate figures, each representing a part of Zimbabwean life. The carvings included the mythical river creature Nyaminyami, the Zambezi River, the mopane tree, the people, and a smoking pipe. Competition among vendors was fierce. The moment we stepped out, we were surrounded, pulled in different directions, items thrust into our hands, and voices calling out offers. For a few minutes, I was completely overwhelmed until my Bombay instincts kicked in.

I knew the drill: ignore the shouting, focus on what you want, and always haggle. Prices started at least three times higher than what we finally paid. My mother, an expert negotiator from years of bargaining with Mumbai street vendors, managed to get us excellent deals. But the strangest part came later. We soon realized that the vendors were less interested in cash than in our belongings. They offered us anything in their stalls in exchange for my backpack, Dwiti’s T-shirt, or Asif’s shoes. One man even offered a beautifully carved wooden mask, easily worth $30, for Seejo’s wet socks.

It was a startling glimpse into Zimbabwe’s collapsing economy, where cash had lost all value and bartering had become the norm. Zimbabwe’s economic downfall was swift. Once, it had a thriving agricultural economy with most farms owned by the white minority. When President Mugabe introduced land reforms to redistribute farmland, ownership was forcibly transferred, often to politically connected members of his own tribe. The new landowners lacked experience in farming, and production plummeted. The economy collapsed, inflation skyrocketed, and the local currency became worthless.

At one point, people carried notes worth 10 or even 50 trillion Zimbabwean dollars, valued at only a few U.S. dollars. Eventually, the country abandoned its currency altogether, and transactions shifted to U.S. dollars, Pula, or Rand.

As we made our way to Hotel Ilala for lunch, Stanley assured us that the economy was slowly improving and that some who had left were returning. The hotel itself was luxurious, with beautifully landscaped lawns, a large swimming pool, and a lavish buffet that stood in stark contrast to the poverty outside its gates. After a delicious meal and a chance to dry off, we began our journey back to Botswana.

Our last stop in Zimbabwe was a crocodile farm. It was immediately clear that this was no wildlife sanctuary but a true farm, where crocodiles were raised for their skins. A young guide named Marvelous (people here had remarkable names; our waiter at Ilala was called “Gift”) showed us around. Large pools held dozens of crocodiles, sometimes piled atop one another. Each pool housed a different age group, with yearlings being the most valuable for their fine skins. Some pools even had chemically treated water to tint the skins red or indigo for specific leather colors.

That was the end of our day. Stanley dropped us off at the Botswana border, where the Chobe Marina staff met us for the ride back to the hotel. Later that evening, as I sat on our small balcony overlooking the Chobe River toward Namibia, it struck me that we had, in a single day, seen four different countries.