It is surprisingly hard to write a travelogue long after the journey is over. The mundane details of the trip such as the time you woke up, what you ate for lunch, the orderly list of “must-see” sights blur together and dissolve into the general fog of memory. What remains instead are the shining moments: the ones that refuse to fade, the ones that define the trip. Perhaps that is how all travel should be written about—after some distance, when only the truth remains. Still, even memory needs a loose framework to hang itself on.

When we began planning our India trip (which, as always, started almost as soon as the previous one ended), I was determined that this time we would take a vacation within the vacation. Somewhere new. And we picked Rajasthan as our destination. Researching Rajasthan, however, is no small task especially when you are married to someone who believes that every day of vacation requires at least three days of high-quality research.

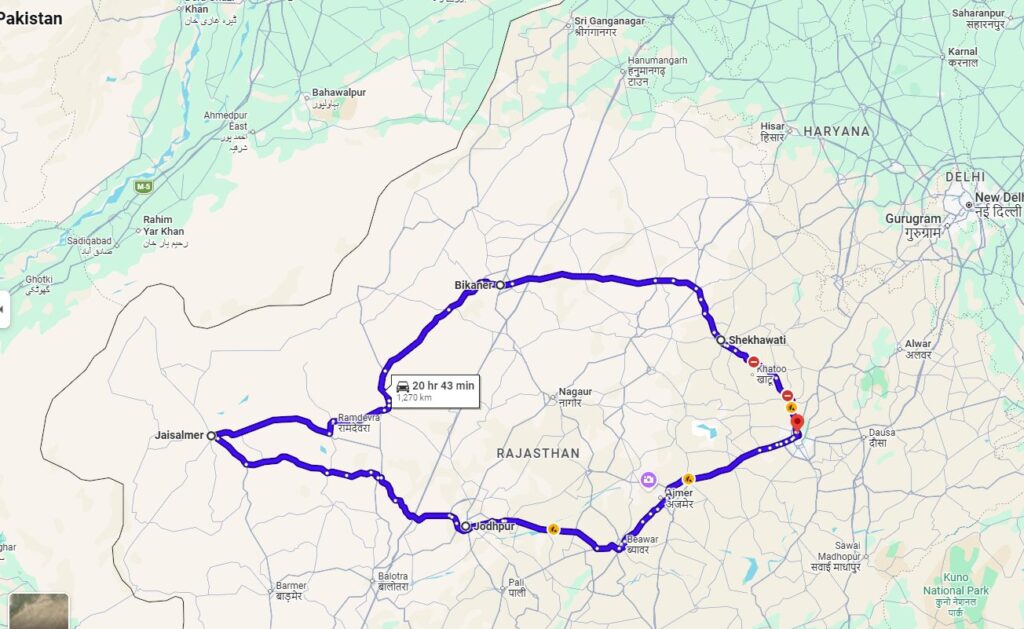

Jaipur was a given: the capital, and conveniently the cheapest city to fly into. But beyond that? Jaisalmer or Bikaner? Ajmer or Jodhpur? Udaipur? Could we squeeze in Sawai Madhopur in a week? Each option demanded debate, spreadsheets (mental and otherwise), and prolonged deliberation. Eventually, a route emerged. Once that was settled, the logistics fell into place easily enough. My mother contacted Tirupati Travels, who offered us a shortlist of hotels in Bikaner, Jaisalmer, and Jodhpur.

We picked what seemed reasonable, and they arranged an Innova with a driver to shepherd us across the Rajasthan. Compared to our usual frenetic style, this itinerary felt almost indulgently relaxed. We would land in Jaipur and spend two days there, then drive west toward Jaisalmer, stopping in the Shekhawati region and Bikaner for the night. After a day in Jaisalmer, we’d head back east to Jodhpur for a day and a half, and finally return to Jaipur.

Our driver was waiting when we landed at Jaipur airport early Saturday morning and took us straight to the Bank Officers’ Guest House. My sister and I still fondly remember earlier holiday homes where resident chefs cooked lavish meals while we lounged in plush suites. Apparently, that memo had not reached the Jaipur office. The rooms were barely clean, cupboards were empty, bed linen was missing, and there was no friendly chef in sight.

But we hadn’t come for the guest house – we’d come for Jaipur. The pink city made its appearance just as we were beginning to complain that everything looked suspiciously beige. Suddenly, rose-colored sandstone buildings sprang up on all sides. The City Palace was expansive but left little lasting impression; what I do remember is the distinctive one-and-a-quarter flag flying above it, marking the Sawai (Sawai means one and a quarter in Hindi) dynasty. The Jantar Mantar observatory was fascinating, the Hawa Mahal , Jaipur’s iconic face, remarkably underwhelming, except for the surprising revelation that its ornate façade is barely one room thick. Amer Fort stood out more, primarily because it was a residential fort, unlike the nearby Jaigarh Fort, which served military purposes. The one historical detail that stuck with me was that the royals would flee from Amer to Jaigarh whenever invasions threatened.

But Jaipur, in my memory, will always be Chokhi Dhani. Over-the-top, unapologetically touristy, and utterly delightful. A carefully constructed version of a Rajasthani village, complete with mehendi artists, camel rides, Ferris wheels, folk dancers, magicians, and even an astrologer whose parrot dispensed fortunes. It was cliché in every possible way, and enormous fun. Seejo, busy fiddling with his fancy cameras, was promptly mistaken for a local photographer, at least two families confidently approached him, ready to hire him for their family portraits. The food was the real star: served on leaf plates, sipped from earthenware cups, eaten cross-legged on the floor while servers urged us to “jeemon, jeemon” (eat, eat) and liberally poured ghee and sugar over moong khichdi as if cholesterol were a fictional concept. The evening ended memorably with my father-in-law attempting to wash his hands with fennel seeds (served as a post meal digestive), having misheard “saunf” (fennel) as “soap.”

After Jaipur, we drove toward Bikaner via Shekhawati. This is where I must introduce Kailas, our driver. Technically excellent, steady, cautious, respectful of speed limits, he even earned Seejo’s rare approval. Socially, however, he was an enigma. Silent, withdrawn, and bafflingly abrupt. He would stop the car without warning, get out, and walk away, leaving us to look at each other in confusion. Is this the next destination? Were we supposed to get out? Or often, it was that he was hungry and had decided it was lunchtime. It was upto us to decide if we wanted to eat too. By the end of the trip, we had learned to read his exits. On the return journey, when he suddenly leapt out of the car again, we were ready to follow-until we realized he had merely ducked behind some bushes for urgent personal business.

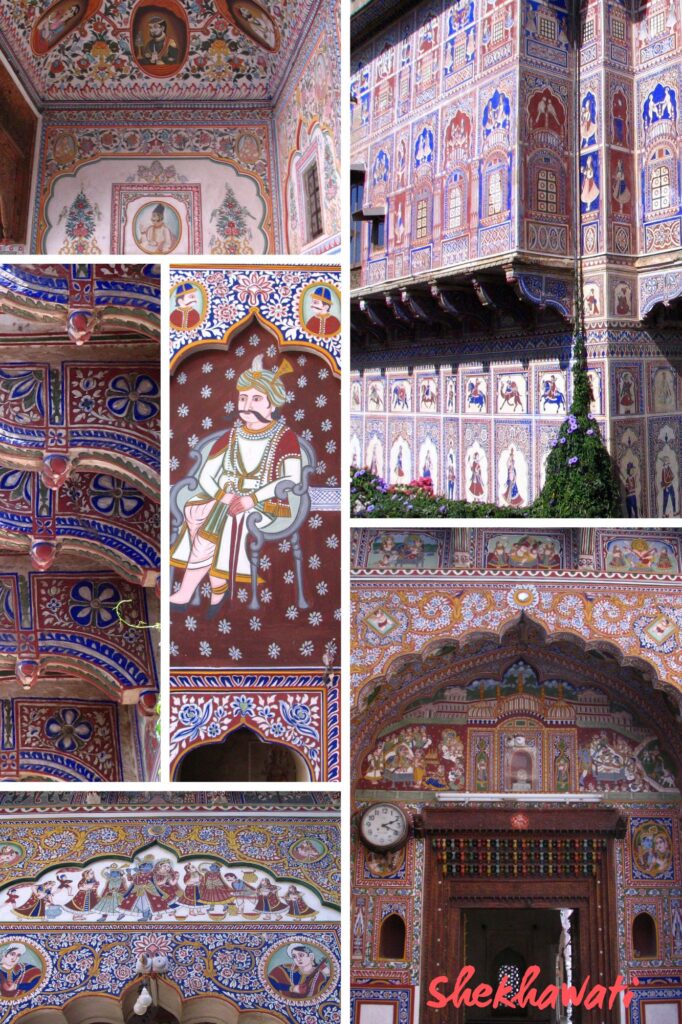

Shekhawati, with its painted havelis (mansions), was the undisputed highlight of the trip for me. Once owned by wealthy traders, these homes are entirely covered in intricate paintings: walls, ceilings, floors, columns, every available surface pressed into service. The colors are natural, the themes wide-ranging: mythological scenes, nature, Mughal and Hindu figures. The descendants of those art loving traders who live in these havelis now cannot afford the upkeep and so the designs have faded away and there is an atmosphere of shabbiness that is very prevalent. But amongst the entire general derelict, there are a couple of houses that showcase the original grandeur of these painted havelis.

One, Angrez ki Haveli (erroneously called the Englishwoman’s mansion), actually belongs to a French artist, Madame Nadine. We were shown around by Shabnam, a lively local girl who switched effortlessly between Hindi and French.

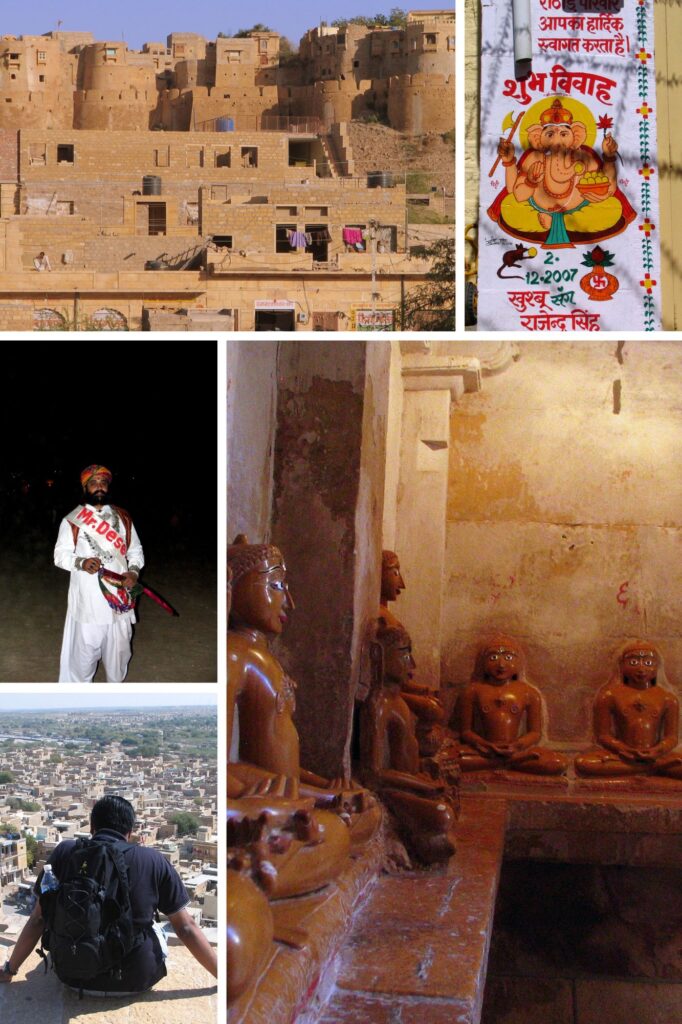

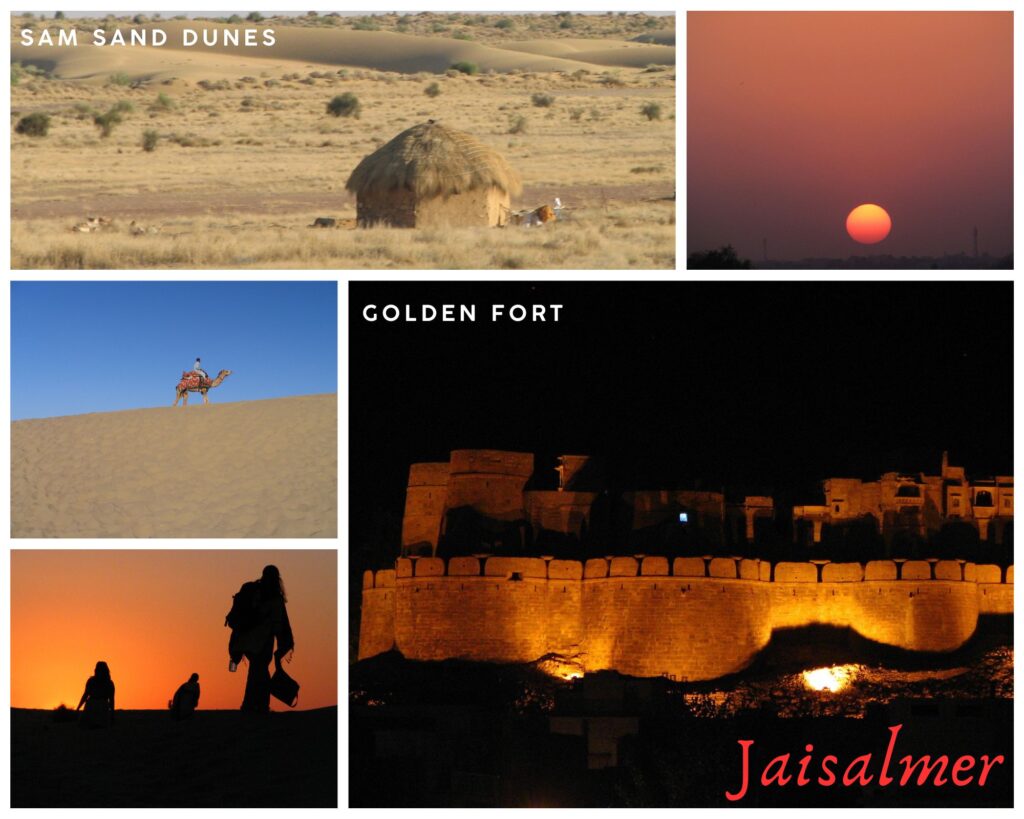

We skipped around the corner to the Singhania Haveli (owned and maintained by the Indian industrialist) and open for tourists. From there we visited Junagarh Fort in Bikaner, pleasant, but unremarkable, and stayed at Harasar Haveli. One of Rajasthan’s great pleasures is staying in these converted havelis: heritage exteriors with modern comforts, and breakfasts of parathas, poori-bhaji, cutlets, poha, alongside continental options. Every hotel was a find, from Jhalamandgarh in Jodhpur to Hotel Moonlight in Jaisalmer, directly opposite the grounds of the annual Desert Festival. By sheer luck, we arrived on the opening night. We crossed the road to hear Vasundhara Das sing, watch children on camel rides, and admire Sonargarh glowing under night lights. We also caught a glimpse of Mr. Desert 2008, who twirled his moustache for us and posed for a photo!

Jaisalmer’s Sonargarh is a living fort- hundreds of families still reside within its walls. Inside, the Jain temple holds rows of identical Tirthankar idols, with each Thirthankar distinguished by a symbol at its base. The highlight of the havelis was their scale and craftsmanship. Many were multi-storied structures-the Patwon Ki Haveli, for instance, is almost like five townhouses fused together, with four floors plus a main level- and their sandstone exteriors were covered in intricate carvings. These havelis once belonged to the king’s ministers, and one of them even had its roof paved in gold. Another detail that caught our attention as we wandered through the bylanes of Jaisalmer was how wedding invitations were painted directly onto the main walls of houses, announcing the marriage of a couple.

According to our guide, they remain there until the next wedding in the family. This public family ledger fascinated us far more than it should have and we spent an inordinate amount of time reading these painted announcements and discovering that one household had just marked an eighth wedding anniversary, while another was preparing for a wedding in just two days.

That evening, we drove into the Thar Desert to the Sam sand dunes. My mother and Dwiti shared one camel, Seejo and I another, both led by a seven-year-old boy who guided us confidently into the dunes. After clicking photos, he wished us luck with our “dansodiner” (dance and dinner ) and vanished speedily, leaving us to guess what dansodinar meant. We found a quiet spot, watched the dunes change color at sunset, and then walked to our desert camp for music, food, and bonfire. The food deserves its own paragraph: dal-baati-choorma, gatta curry, ker-sangri, kadhi-pakodi, kachoris, bajra rotis. My in-laws eyed each dish with suspicion, mourning the absence of dosa, while the rest of us ate with wholehearted enthusiasm. We slept in tents, woke early for sunrise, and discovered that the dunes existed only within a finite patch, surrounded by scrubland where deer roamed freely.

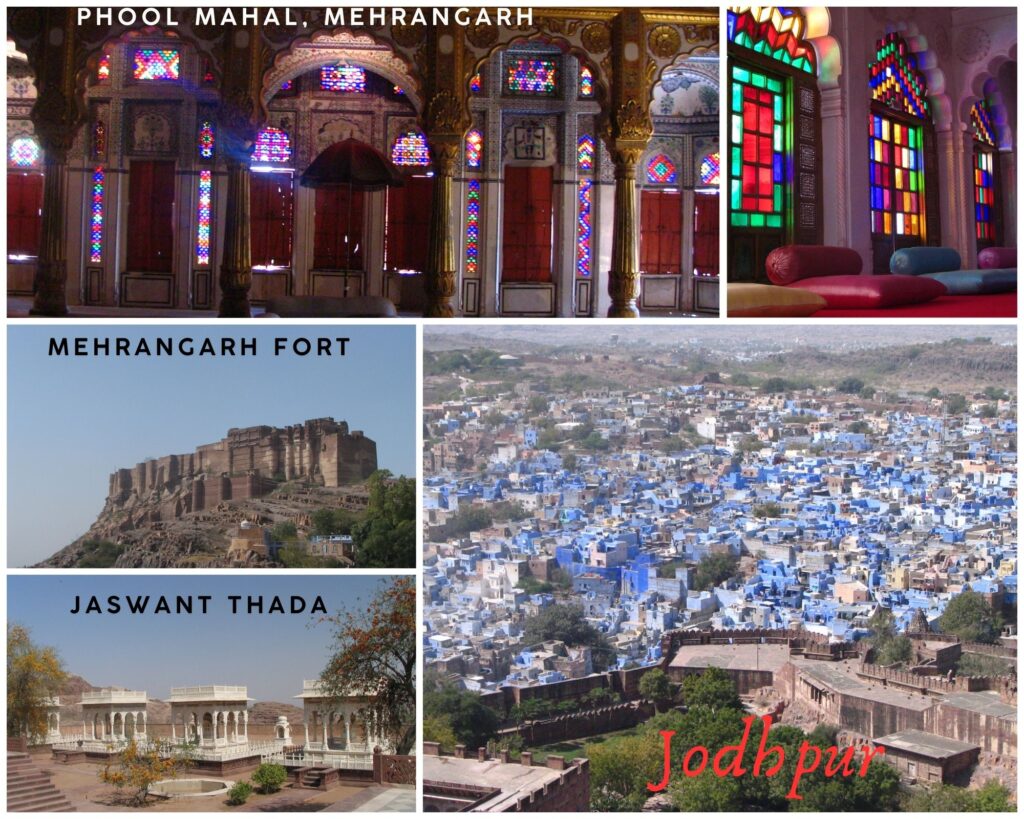

Camels were everywhere, the standard mode of transport for locals and a novelty for tourists. We saw them even on the roads to Jodhpur, ambling along the roadside, paying scant attention to passing cars or heavily loaded trucks, which were themselves a sight, often carrying loads that seemed three times larger than the trucks themselves. In Jodhpur, we visited Mehrangarh Fort, Umaid Bhavan, Jaswant Thada, and looked down at the Blue City – a wash of royal blue rooftops, each subtle on its own, breathtaking in aggregate.

What makes Rajasthan especially welcoming and tourist friendly are its guides – knowledgeable, multilingual, enthusiastic. Each added texture and context, but the standout was our Jodhpur guide. He proudly told us that the film Zubeida was based on the present king’s father and that she had lived in this very palace. He pointed out where songs from Hum Saath Saath Hain were filmed in the central courtyard of Mehrangarh and then launched into a passionate critique of Jodhaa Akbar. His main grievance was that while Akbar may have married a Hindu, and perhaps even a woman named Jodha, she was certainly not Raja Mansingh’s sister. He was clearly appalled by what he saw as Indians learning a British version of their own history and declared, with great conviction, that it was all “bilkul galat baat hai.” According to him, Raja Mansingh’s sister had actually married Akbar’s son. He did, however, concede my point when I asked whether Hrithik Roshan and Aishwarya Rai playing a father and daughter, would have sold quite as many tickets.

That evening we also visited a Bishnoi village. The Bishnois are a tribal community known for their deep commitment to protecting local wildlife. They came into national prominence when they sued actor Salman Khan and others for shooting an endangered black buck. One of the villagers took us on a jeep safari through the area. Deer and peacocks were everywhere, and the villagers provided them with water and allow them to graze freely on their land, gently driving them away from crops when needed.

We even spotted a rare black buck in the distance at a watering hole. We also visited the village potter and tried our hands at pottery, quickly learning that the hardest part is lifting the pot off the wheel without completely squishing it.

We returned to Jaipur on a gleaming expressway, passed Ajmer from afar, and ended the trip shopping ourselves silly in Bapu Bazaar. All in all, it was a wonderful journey – and the longest I have been separated from my laptop in five years. Astonishingly, I didn’t miss it at all.